stumbling into aerodynamics

Home Posts About Me

We can think about air in several ways. We know it is a collection of gases and particles which are all molecules. When something moves through the air, it makes contact with each of these individual molecules. The extent to which the individual collisions matter varies based on the size of the particle, density of the air, speed of the particle motion, and the size of the aircraft.

To describe this conundrum, we can use the concept of a mean free path. The mean free path is best described as the average distance molecules in a control volume travel before encountering another. This can be approximated using the factors discussed earlier, but the actual equation is not important in this context. (It's also not entirely accurate because of the difficulty of ascertaining the diameter of a molecule; are the electrons really in only one place? How do we measure that position?)

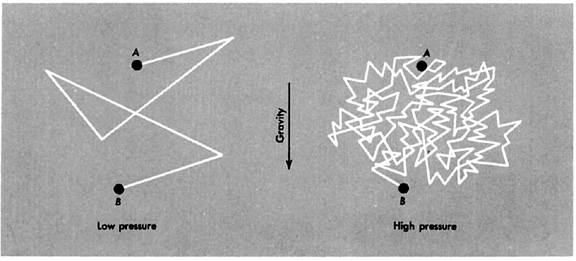

Molecule Paths

The graphic above depicts molecule paths in low and high pressures. As you can see in this representation, each molecule travels in a straight line (let's ignore gravity) until it hits another molecule. This would occur at every turn in the path. In a low pressure environment, there are not very many gas molecules, so there are fewer collisions. As the pressure, \(p\), and the density, \(\rho\), increase, collisions become more and more frequent, and the mean free path decreases.

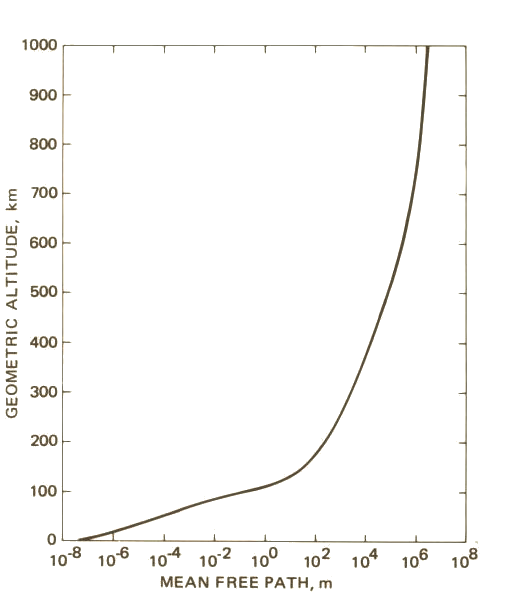

Altitude vs. Mean Free Path

This graph makes mean free path look incredibly significant. If you're flying at an altitude of 1000 km, air molecules collide on average after traveling 1,000,000 meters?! This actually isn't so concerning for the vast majority of flight because most crafts are limited to an altitude of about 14 km. At this altitude, the mean free path only just starts to rise from a tenth of a micrometer.

So all aerodynamic forces are due to collisions with particles, right? How do we calculate these if a particle collides every time it travels a tenth of a micrometer?

Not all of this data is significant. Much of it can be approximated. Rather than considering each individual molecule in every calculation, analysis can be done on all of the molecules as a continuum. This is treating the fluid as a continuous data set instead of a discreet one.

Raster vs. Vector

Molecular vs. Continuum

Discreet vs. Continuous

A good example for this kind of data is the representation of graphics as either raster or vector files. One uses a collection of many data points while the other simply uses a set of functions to describe the same set.

Most of aerodynamics with aircraft with use the continuum model of fluids, but as nanotechnology advances and non-passenger aircraft shrink, there might be appropriate applications to which the molecular model can be applied.

--Aryn Harmon